Sunday 26 February 2017

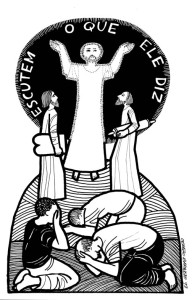

Transfiguration Sunday

Exodus 24:12-18, Matthew 17:1-9

On this Sunday, every year, we celebrate the festival known as the Transfiguration of the Lord. It is the day we remember Jesus, up on the mountain with his three closest disciples, Peter, James, and John, surrounded by a divine cloud, visited by Moses and Elijah, transformed in appearance. This Sunday, though, I’d like to focus on one of our other readings in order to get a better perspective on Jesus’ transfiguration.

When one text in the bible harkens back to another text in the bible, we call that intertextuality. The story of the transfiguration depends on a great amount of intertextuality. One of its intertexts is the story we read today from the book of Exodus And exploring that story from Exodus is going to give us a much better understanding of the transfiguration story, that is partly based upon it.

Exodus, as you may know, recounts the story of Moses leading God’s people, the Hebrews, out of slavery in Egypt and toward their new home in the promised land. This particular part of the story happens after the people have been freed and left Egypt. God has led them to a great mountain, where God’s presence dwells powerfully.

As you may know, Sinai is where God granted the holy law to God’s holy people. We know that Moses went up on the mountain and received the ten commandments. When he came down later, the Israelites were worshipping a golden calf and Moses broke the stone tablets of the law.

If you try to read the account in Exodus, though, it’s a lot more complicated than that. The whole encounter starts in chapter 19. By chapter 20, God is speaking the words of the law. God keeps on talking all the way into chapter 24. Then we get to the bit we read today, which is followed by more instructions from God. Moses doesn’t come down off the mountain to find the golden calf until chapter 32. Over the course of those 12-chapters-worth of commandments, it’s hard to keep track of who is on the mountain, who is off the mountain, or where on the mountain various people are.

At the beginning of our chapter, chapter 24, Moses goes at least part way up the mountain along with Aaron and several elders. We are told that all of these elders saw God, even though just a few verses before it was claimed that they would not be allowed to see God. Then, we are told that Moses and Joshua went up the mountain to receive the stone tablets. Did they just go farther up the mountain? We don’t know. All of the commandments have already been spoken. Did everyone hear them? It’s not clear.

In any case, at this point in the story, we are told that Moses and Joshua go up the mountain to receive the tablets. Presumably the elders stay at some point farther down the mountain. Then we are told again that Moses goes up the mountain, this time with no mention of Joshua. It’s all very confusing.

Clouds begin to cover the mountain. We had been told the same thing at least two times before, but again, clouds cover the mountain. God’s presence, which is usually described as looking like fire, is also on the mountain. Is Joshua up there with him? Maybe. He seems to come back down the mountain with Moses eight chapters later, but he doesn’t do much in the intervening time.

Moses has gone up to get the stone tablets that God has inscribed with the law. But he doesn’t get them right away. He just stays up there in God’s presence for six days and we aren’t told what happens. On the seventh day, a voice comes out of the cloud and calls to Moses. Then we are told for a third time in these very few verses that Moses goes up the mountain.

So, to review our tiny section of chapter 24, Moses goes up the mountain with the elders. They see God, and they have a meal. Then a cloud comes upon the mountain, and Moses goes up the mountain with Joshua and enters the cloud. He waits for six days. On the seventh day, God calls from the cloud and Moses goes up the mountain. He stays there for forty days and forty nights.

The point I’m trying to get across is that this narrative doesn’t make much sense. Everything is jumbled. We could work really hard unravel the complexity of all of the strange details, but really, this section of Exodus just defies understanding.

And perhaps that is understandable. After all, this passage is trying to describe a direct experience of God. It’s no wonder that it’s hard to make sense of. It’s no wonder that everything seems confused and confusing. This is the most important event in the Hebrew Bible. This is when God makes a covenant with God’s people. This is when God grants the law and the instructions that have guided the lives of billions of people. That kind of an experience cannot be explained or contained by a simple narrative. It’s no wonder, when it comes to such an indescribable event, that the biblical writers have a hard time describing it.

A couple of millennia later, Jesus leads some of his disciples up onto a high mountain. “Six days later,” the passage begins, reminiscent of the six days Moses waited. He brings with him his inner circle: Peter, James, and John. It gives bit of the sense of the layering that we got on Mt. Sinai, with the people on the plain, the elders a little higher up, and Moses with his most trusted advisor up a bit farther. Presumably, something similar happens here, with the people and crowds below, the disciples up a little closer, and Jesus and his three closest disciples farther up the mountain. His face begins to shine. It’s not unlike Moses, whose face would shine after he had conferred with God in the tabernacle. His clothes turn dazzlingly white. Moses and Elijah suddenly appear alongside Jesus. Of course, we are not surprised that Moses is there.

The three disciples are a bit dumbstruck. They know that this is the sort of thing that hasn’t happened since the time of Moses. They know the stories of Moses on the mountain, in the presence of God, receiving instructions directly from God. They know that this is no ordinary mountain and that they are having no ordinary experience.

Peter, who is the only one who can manage to speak, suggests that he could build three shelters for Jesus, Moses, and Elijah. During the festival of Sukkoth, Jews build little shelters and live in them for a week to remember the forty years that Israel spent in the wilderness. So, Peter offering to build these shelters means that he expects another Sinai. He knows that this is some kind of direct experience of God. He expects that God is going to give a new law, just like God gave to Moses on the mountain at Sinai.

While Peter is still talking, all of his suspicions are confirmed. Suddenly a bright cloud appears on the mountain, the glorious presence of God, just like it appeared on Sinai centuries before. And then a booming voice speaks from the cloud, the voice of God, just like it spoke from the cloud on Sinai.

This divine voice has a message about Jesus. “This is my Son, whom I dearly love. I am very pleased with him. Listen to him!” In other words, Jesus is the expected Messiah. He can speak directly to God, like Moses did. And he is a new lawgiver, a new Moses. Listen to him. Listen to his instruction, just as the people listened to the instruction of Moses long ago. And of course, this reminds us of the mountain top experience that we have been hearing in the gospel readings for the last month—the Sermon on the Mount—when Jesus takes on the role of lawgiver, just like Moses did centuries before.

Nearly every word of Matthew’s story of the transfiguration harkens back to the story of Moses on the mountain. And the story of the transfiguration is just as confusing as the story of Moses. Things appear and never disappear. But it’s the sort of thing that we should expect of a story about a direct experience of God. Those sorts of experiences never make sense to the rational mind; they can never be explained in mere words.

This story of the Transfiguration, taken on its own, is impressive. It reveals the divine identity of Jesus. It shows him in his glory. But when we read it along side the story of Moses at Sinai, it becomes much more rich. Suddenly the lights and the smoke and the special effects take on a new meaning. Jesus, and the covenant that he represents, is tied intimately to Moses and the covenant that he represents. Jesus is a new thing, but he is also tied to the old. He takes the covenant offered to God’s chosen people, and he expands it. He offers gentiles a chance to become part of God’s family. But he does not abolish Moses or the old covenant. He does not abolish it, he simply expands it, and he offers us the chance to be a part of the special relationship that God has already established with the Jews.

Jesus makes a new covenant. In it, God promises to be our God, to accept us as God’s people, to forgive us, lead us, bless us, listen to us, guide us, change us, redeem us. And we promise to be God’s people, to seek God in our prayers, in our praise, in our searching the scriptures, in our interactions with neighbors, in the way we use our money, in the ways we offer our service, in the choices we make, in the ones we love.

In Jesus, God makes a new covenant with us, a covenant that is founded on the older covenant with Moses. And in it, we find the foundations for the other covenants in our lives. The covenant God has with us informs the sacred covenant between spouse and spouse, the sacred covenant a parent has with a child, the sacred covenant we share within this congregation, the sacred covenant we share with those in our community, the sacred covenant we share with all of God’s children, no matter where they come from, what language they speak, or how they worship.

In the transfiguration, we see and remember the covenant God has with all people. We see and remember the covenant we share with each other. And we are called to live as children of the covenant, who worship God as our God and who seek always to be God’s people, formed by the love God has shared with us, and moved always to share that same love with everyone we meet. Thanks be to God.

More than twenty years ago, Robert Bellah described how Americans were adopting

More than twenty years ago, Robert Bellah described how Americans were adopting